What is the secret of a beautiful nose? Is it just about having a flawless appearance, or is it about enabling comfortable breathing for a sound sleep at night? In fact, there isn’t a single correct answer to this question. Because the nose is a perfect organ where aesthetics and function are inseparable and intricately intertwined. Located right in the center of our face, it is not only an aesthetic signature that defines our expression and character but also the gateway for breathing — the very first act of life. Therefore, approaching the nose as a whole — understanding both its external shape and its internal function — is an absolute necessity for the success of any surgical intervention.

Why Is the External Structure So Important in Nose Aesthetic Surgeries?

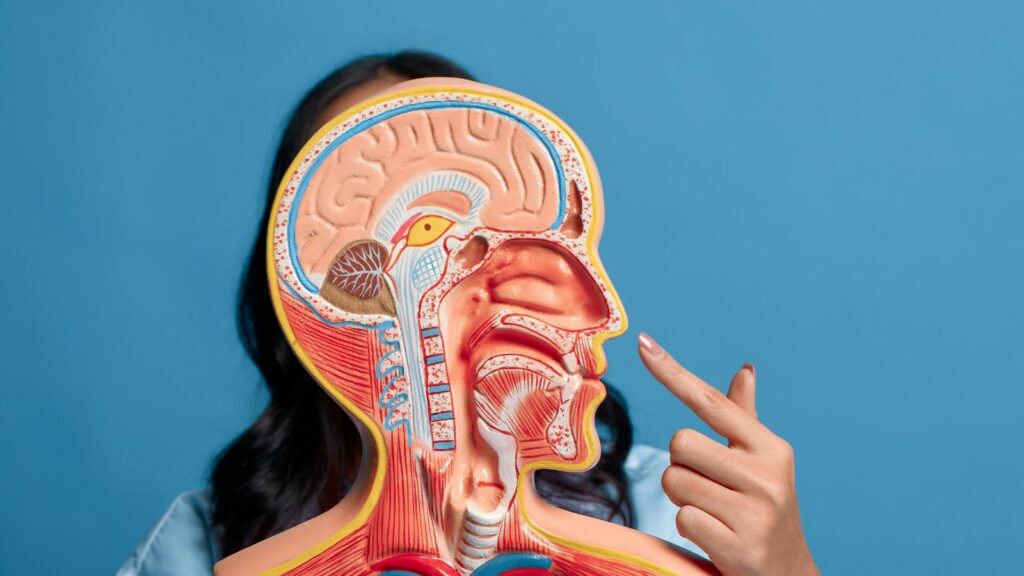

The shape of our nose that we see from the outside is actually like a garment draped over a complex skeleton beneath. This skeleton determines both the aesthetic stance and provides the structural stability of the nose. Just as a building’s façade looks flawless when its foundation and columns are strong, the same principle applies here. That’s why, in nose aesthetic surgeries, the surgeon’s first focus is this fundamental skeletal structure.

The nasal skeleton consists of three main parts:

- Upper Part (Bony Roof)

- Middle Part (Cartilaginous Roof)

- Lower Part (Nasal Tip)

These three sections work in harmony as an architectural masterpiece. At the top, between the eyes, lies the hard and stable bony roof. This part determines the general posture and width of the nasal bridge. In aesthetic surgery, controlled bone cutting and shaping (osteotomy) provide a more elegant and harmonious appearance with the face. The millimetric precision in this process directly affects the naturalness of the result.

Just below that lies the semi-flexible cartilaginous roof. This area continues the nasal bridge and houses the internal valve — one of the most critical points of the airway. Especially in surgeries where the hump on the nasal bridge is corrected, maintaining the support of this middle roof is vital. If this support is weakened, it may collapse over time, leading to both aesthetic problems (inverted V deformity) and serious breathing difficulties.

At the bottom is the most dynamic and mobile part — the nasal tip. The shape, height, refinement, and nostril form of the tip depend entirely on the structure and strength of the cartilages (lower lateral cartilages) located here. These cartilages act like poles holding up a tent. The secret of a successful rhinoplasty is not to weaken these support mechanisms, but to reshape or strengthen them to prevent the tip from drooping over time.

What Is the Skin Thickness Factor That Affects Rhinoplasty Results?

Imagine a sculptor carving marble into a masterpiece. During rhinoplasty, the surgeon shapes the bone and cartilage framework much like an artist. However, the nature of the covering that will be draped over this sculpture determines how the final result will look. The nasal skin serves as this covering. The thickness and quality of the skin are among the most critical factors determining surgical success and directly influence the surgeon’s strategy from start to finish.

If you have thin skin, it acts like a silk veil. Even the smallest modification underneath, the tiniest detail, becomes clearly visible on the outside. This is both an advantage and a disadvantage for the surgeon. It’s an advantage because delicate, well-defined results can be easily achieved. But it’s a disadvantage because even the slightest irregularity or asymmetry beneath can immediately show through. Therefore, for patients with thin skin, the surgeon’s work must achieve absolute smoothness and symmetry.

Thick and oily skin, on the other hand, behaves like a thick wool blanket. No matter how finely the skeleton underneath is sculpted, thick skin tends to hide and soften those details. In this case, the surgical strategy changes. The goal becomes building a strong, well-supported, and sufficiently projected cartilage framework that can still be seen beneath the skin. Otherwise, the nasal tip may fail to appear refined and, with postoperative swelling, may gradually develop a rounded, parrot-beak-like appearance known as “pollybeak deformity.” Therefore, surgical planning must be individualized, and your skin type is one of the most fundamental determinants of this plan.

How Is the ‘Aesthetic Subunit Principle’ Applied During Nasal Reconstruction?

Especially after trauma or skin cancer surgery, when tissue loss occurs in the nose, reconstructive surgery comes into play. At this point, a brilliant concept called the “aesthetic subunit principle” takes aesthetic outcomes to another level. According to this principle, the nose is divided into aesthetic regions separated by its natural shadows and contours.

The nasal aesthetic subunits are:

- Nasal bridge (dorsum)

- Nasal tip (tip)

- Columella (the area between the nostrils)

- Alae (wings of the nose)

- Lateral walls

Soft triangles

The core idea of this principle is: if tissue loss involves more than half of one of these subunits, the best result is achieved by removing the remaining healthy portion of that unit and reconstructing the entire subunit as a single piece. When surgical scars are hidden within these natural borders, they become virtually invisible. This approach turns the body’s natural healing mechanism from a disadvantage into an advantage. If a simple “patch” is placed in the middle of a subunit, the scar tissue around the patch may contract over time, causing a sunken, patchy look. However, when the entire subunit is replaced as one piece, the contraction forces distribute evenly over the surface. Instead of collapse, this creates a subtle convexity that mimics the natural curvature of the nasal wing or tip. This is not just a scar-concealment method but the art of using wound-healing physics to achieve aesthetic beauty.

What Are the Symptoms of Septum Deviation That Cause Breathing Difficulties?

The inside of our nose is as important as its exterior because breathing — its primary function — happens there. The wall that divides the inside of the nose into two separate air passages is called the “septum.” Ideally, this wall, made of cartilage in the front and bone in the back, should be positioned right in the middle. However, due to congenital reasons or trauma, it may bend to one side. This condition is called “septum deviation.”

This curvature narrows one airway, making it harder for air to pass through and leading to problems that seriously affect quality of life. Common symptoms of septum deviation include:

- Persistent nasal congestion (usually one-sided)

- Snoring

- Sleeping with the mouth open

- Frequent sinus infections

- Postnasal drip

- Occasional headaches

Decreased sleep quality and fatigue

The solution to this problem is “septoplasty” surgery. In this procedure, the deviated cartilage and bone are corrected or repositioned through the inside of the nose to open the airway. Since no external incision is made, there are no visible scars, and the shape of the nose does not change.

What Causes Turbinate Hypertrophy, Known as ‘Nasal Concha Enlargement’?

The structures known as “turbinates” — often referred to as “nasal conchae” or “nasal flesh” — are bone structures covered by mucosa on the side walls of the nasal cavity. They function much like the radiators in our homes. Their main job is to warm, humidify, and filter the incoming air. Thanks to their large surface area, they can condition even the coldest and driest air to make it suitable for the lungs.

However, in some cases, these “radiators” can enlarge excessively and block the airway — a condition known as “turbinate hypertrophy.” The main causes of turbinate enlargement include:

- Allergic rhinitis

- Chronic infections

- Environmental factors such as air pollution

- Compensatory enlargement due to septum deviation

The last point is particularly interesting. If the septum is bent to one side, that side narrows while the opposite side widens excessively. The body perceives this abnormal width as inefficiency and tries to compensate by enlarging the turbinate on the wider side. Therefore, simply correcting the septum is sometimes not enough. The surgeon often needs to reduce the enlarged turbinate on the opposite side — using methods like radiofrequency (turbinoplasty) — to balance both airways for complete functional recovery.

Could Persistent Congestion After Surgery Be Caused by Nasal Valve Collapse?

The narrowest point in the nasal airway is called the “nasal valve.” It’s a critical area where the greatest resistance to airflow occurs. You can think of it like a highway suddenly narrowing into a single lane. No matter how wide the rest of the highway is, traffic will jam at that bottleneck.

There are two important valve areas in the nose — internal and external. The internal valve is the angle between the nasal middle roof and the septum, while the external valve corresponds to the nasal wings. If the cartilage supports in these regions are weak, they can collapse inward due to the negative pressure that occurs during breathing. This condition is called “nasal valve collapse.” It is a dynamic functional problem rather than a static blockage.

Situations suggesting a nasal valve issue include:

- Inward collapse of the nasal wings during deep inhalation

- Increased shortness of breath during exertion

- Noticeable relief in breathing when the cheek is pulled outward with a finger (Cottle Maneuver)

- Persistent congestion despite a successful septoplasty

In many patients who have undergone septoplasty yet still experience nasal obstruction, the underlying cause is an overlooked valve problem. The solution is not removing tissue but rather reinforcing this weak area with cartilage grafts to restore proper structure.

What Anatomical Risk Factors Contribute to the Development of Chronic Sinusitis?

The sinuses are air-filled cavities within our facial bones. Their health depends on the continuous openness of the narrow drainage channels that allow mucus to exit. The junction point where the drainage channels of the front group sinuses (cheek, forehead, and between the eyes) meet is called the “Osteomeatal Complex” (OMC). This is the key to sinus health.

Some people are born with structural variations that further narrow this tight junction. Although these are not diseases themselves, they act as “risk factors” for chronic sinusitis. When conditions such as viral infections or allergic reactions cause the mucosa to swell, these already narrow areas can become completely blocked, leading to sinusitis.

Some common anatomical variations that can narrow the OMC region and predispose to sinusitis include:

- Concha bullosa (air inside the middle turbinate)

- Haller cell (extra air cell beneath the eye)

- Paradoxical middle turbinate (curving outward instead of inward)

- Large ethmoid bulla (overdeveloped air cell between the eyes)

The philosophy of modern sinus surgery (FESS – Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery) is not to scrape the inside of the sinuses but simply to open this blocked main drainage junction (OMC). The principle is simple: if you unclog the main drainage pipe in a plumbing system, the upper floors will drain themselves. Likewise, when the sinuses’ natural drainage pathway is reopened, the inflamed mucosa inside heals naturally through the body’s own mechanisms.

What Are the Causes of Frequent Nosebleeds and What Does the ‘Danger Triangle’ Mean?

Our nose has a rich network of blood vessels supplied by both the internal and external branches of the carotid artery. This dual blood supply is an excellent feature that accelerates healing after surgery. However, it also explains why nosebleeds (epistaxis) are so common and sometimes severe. Especially the front part of the septum, known as “Kiesselbach’s Plexus,” where many vessels converge, is the source of 90% of nosebleeds in children and young adults.

An important concept to know about the nose is the “danger triangle” of the face. The veins in the triangular area connecting the nasal root to both corners of the upper lip lack valves that prevent backward blood flow. This anatomical feature means that a severe infection in this region (such as an inflamed pimple or folliculitis) carries a rare but serious risk of spreading to crucial venous structures in the brain (the cavernous sinus). Therefore, infections in this area should never be squeezed and must always be taken seriously.

What Are the Vital Functions of the Nose Besides Breathing?

Our nose is much more than a simple airway. It is like a high-tech air-conditioning system that perfectly prepares the air for our lungs. This system has several essential roles:

The main functions of the nose include:

- Filtering the air

- Humidifying the air

- Warming the air

- Smelling

Defense system (mucociliary clearance)

After passing rapidly through the narrow valve region, the air slows down as it creates whirlpools (turbulence) in the wider nasal cavity. This is an intentional design — it increases contact time with the mucosa to ensure effective conditioning. Inside the nose, the “mucociliary clearance” system — a moving escalator made of microscopic cilia — continuously traps and transports dust, microbes, and allergens toward the nasopharynx. Smelling, on the other hand, occurs at the very top of the nasal cavity, in a protected “attic” separated from the main airway. This way, the delicate olfactory nerves are shielded from the harsh effects of direct airflow. The direct connection between the sense of smell and the brain’s memory and emotion centers explains why a scent can instantly transport us back to a moment from years ago.

How Is the Balance Between Aesthetics and Function Achieved for a Successful Nose Surgery?

In light of all this information, it becomes clear that nasal surgery has more than one dimension. Whether rhinoplasty, septoplasty, or sinus surgery, every procedure depends on a delicate balance between related systems.

A surgeon performing an aesthetic nose operation (rhinoplasty) must also think like an aerodynamic engineer, ensuring that aesthetic changes do not narrow the airway.

Similarly, a surgeon performing a functional surgery (septoplasty) to open the airway must also act like a structural engineer, ensuring that removing cartilage does not compromise the nasal roof’s integrity.

Thus, the fundamental philosophy of modern nasal surgery is to consider form and function as a whole. The goal is to create not just a nose that looks beautiful from the outside, but one that also performs all its vital internal functions flawlessly — a nose that is both aesthetically and physiologically healthy. Success lies in the perfect balance between these two elements.